Moving toward a more proactive and preventative system of care

One of the big, consistent messages coming out of discussions at this year’s NHS ConfedExpo was the need to go further and faster in achieving the crucial “left shift” to a more proactive and preventative system of care. But how?

What came across, particularly in Amanda Pritchard’s keynote speech, was that a more value-based approach to planning and commissioning was a key enabling force.

In her words, one of the challenges ahead was to “incentivise the right care in the right place [and] reward all the providers involved…for making best uses of resources and for improving quality.”

It seems clear then, that the principle of value-based care (VBC) remains vital for a health and care system unlikely to be blessed with bountiful injections of cash or people anytime soon.

(And, of course, it’s absolutely the right thing to do for our patients and populations, too.)

Yet as Pritchard herself admitted, all of this is proving much harder to achieve in practice. So, what are the critical areas integrated care systems (ICSs) need to address if they want to move forward with VBC?

Mapping out the patient story

The first is having the right data.

Value-based care must start with a clear consensus on where the potential value lies within a given pathway and what this looks like from a patient and system perspective — reflecting less unplanned care, more proactive and preventative interventions and more efficient use of resources that deliver improved patient experience and ultimately improved outcomes.

However, you can only get there if you have a robust, linked data set telling you the story of a patient’s journey through the system and identifying the critical touch point and the costs incurred along the way.

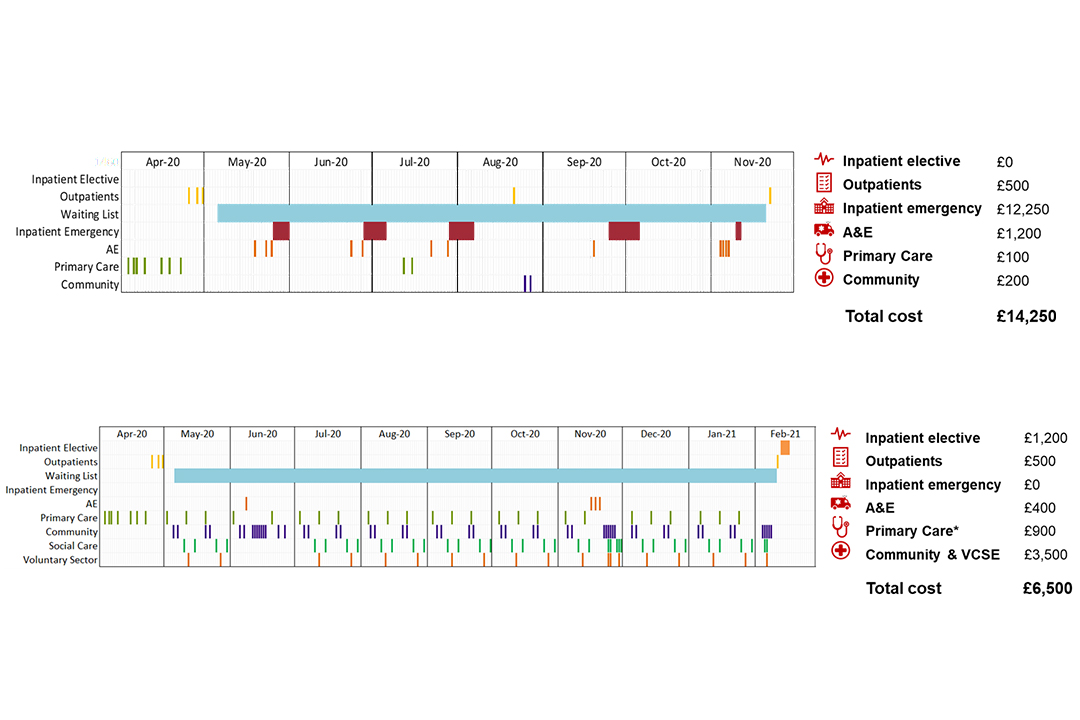

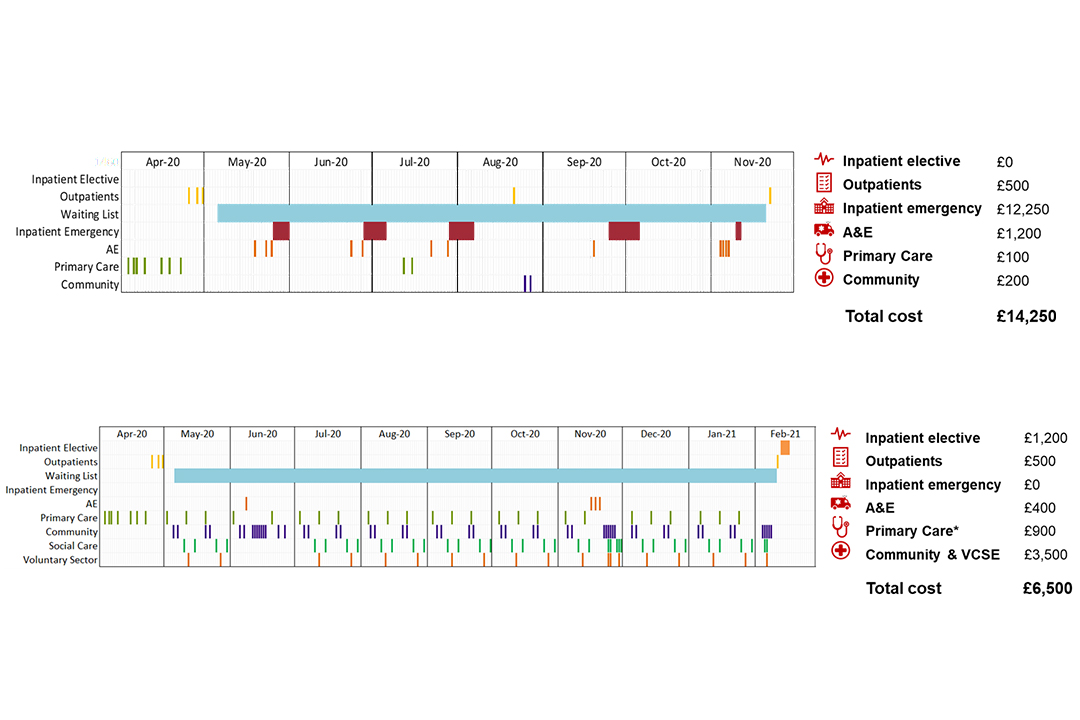

Using a theograph to map this journey can be a powerful way of exposing where opportunities are to reallocate resources or redesign a pathway to reduce more costly interactions with the NHS.

With the right data and tools, you can see — and measure — the projected differences in a patient’s journey through the system and how this translates into cost.

For example, if you take a person with complex medical and social needs, this can lay bare the financial gains that can be made from moving away from a reactive pathway with little community-based support resulting in multiple instances of unplanned hospital admissions — to a more integrated service that provides regular (and if necessary) more assertive care in a community setting (figure 1).

Illustrating a patient’s journey through the system

Theographs illustrating the difference between a reactive pathway (top) and an integrated, proactive model (bottom).

Two theographs; the top illustrates the patient activity and cost when on a reactive pathway and the bottom illustrates the patient activity and cost when following a proactive pathway.

Scaling up a value-based approach

The next big challenge is scaling up to larger scale transformation involving multiple interventions, larger cohorts, and place and system-level change.

While there are some notable examples – such as the “new model neighbourhood” being developed in Sheffield, or the systematic efforts across Lincolnshire ICS to apply population health management principles in all its planning processes — this is where value-based care struggles to break through.

Part of the problem relates to culture and capability — that is, how we move people and their organisations away from a focus on cost savings and efficiencies so that value is at the centre of how they think about planning, commissioning, and delivering services.

It takes time and effort to shift the mindset and ground these data-driven, population health management principles into people’s everyday practice.

Yet arguably an even bigger issue involves financial management. As Amanda Pritchard described, “doing” value-based care at scale involves fundamentally rethinking the way Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) contract and incentivise services to drive the right outcomes — for citizens and patients, and for the models of care we need to establish.

It’s extremely welcome to see these signals come from the very top at NHS England — and the challenge now is to embed these more sophisticated value-based contracting models on the ground.

Without this close alignment between the strategic outcomes the commissioner is aiming to achieve and the financial parameters it is asking providers to work within, what often happens is that demonstrably good and value-adding local projects become isolated or are simply allowed to wither on the vine.

A practical roadmap

A third and final area is having a clear, practical roadmap for change.

With the right data and analysis, it’s possible to model out different scenarios and make them feel that much more tangible for the stakeholders we need to bring with us on that change journey.

Because it is a journey, and potentially a long one. But a focus on value-based care — with population health management (PHM) as its engine — is a means of giving people the confidence and the appetite for that change.

Furthermore, if we think of value-based care as a series of steps rather than a wholesale change, it becomes more achievable: Start with the data, build the evidence, achieve consensus on the value you want to see, make the change, measure the impact, and work on the shift in culture, which in turn will allow for a redesign of incentives.

In short, if we can get these three things right — the data, the money and the people — then we can really propel VBC forward with intent.

And that's ultimately how we start to move this agenda beyond the conference hall — as a practical, well-grounded philosophy that enables us to make the necessary shift from reactive to proactive and preventative care.

About Victoria Underhill

Victoria has over 18 years of experience of healthcare management with a focus on population health management, finance, commissioning, quality and information.

About Bec Richmond

Bec is director of PHM and value-based care at Optum UK. She helps integrated care systems develop and implement sustainable PHM strategies.

This article was prepared by Victoria Underhill and Bec Richmond in a personal capacity. The views, thoughts and opinions expressed by the author of this piece belong to the author and do not purport to represent the views, thoughts and opinions of Optum.